|

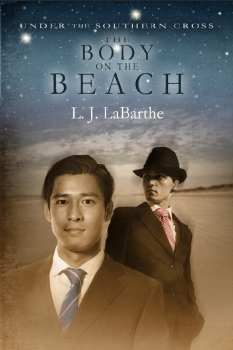

THE BODY ON THE BEACH by L.J. LaBarthe

reviewed by Mel Keegan

ISBN-13: 978-1-62380-549-4

Pages: 109

Cover Artist: Anne Cain

Publisher: Dreamspinner Press

Intrigue and mystery in the Chinese community, and a dead body in the shallows under the jetty at Brighton. It’s a delicious premise for a novel, and how could I resist, since I’ve lived in this area for many years?

Mention ‘The Body on the Beach’ to a South Australian over the age of 40, and the mind immediately recalls a very real murder mystery known locally by that name, which remains a vivid part of the state’s folklore. The real-life body was found on the Semaphore beach, north up the coast from Brighton; and on his person was a half-page torn from a book, printed with the words ‘Tamam Shud,’ which caused a stir. No one attached to police or media at the time knew the last page of The Rubaiyat of Ohmar Khayyam when they saw it. Eventually, someone must have picked up a phone after the story appeared in the papers … not me! It was a bit before my time. All this happened in 1948. (Interested? See this.)

The Body on the Beach by L.J. LaBarthe is set in the 1920s, and borrows the title of the folkloric incident and the mysterious slip of paper; but LaBarthe’s unknown deceased is discovered bobbing in the waves under the jetty down at Brighton, and has a Chinese character carved into the flesh of his chest -- immediately linking the murder to Adelaide’s Chinese community, with the potential to generate a wave of racial hysteria.

Enter William “Billy” Liang, lawyer and businessman, and his partner in both business and life, Tom Williams, solicitor, who spend several days in the late February heat -- the tail-end of summer down here -- hunting for evidence to convict the killers and divert attention and hostility from the state’s Chinese population.

It’s a marvelous premise for a detective novel, and the author could have dug deep, exploring the world of Chinese Australia. I’d been hoping for this, but the novel -- though a competent mystery -- only skims the surface of the potential with a simple, straight-forward plot, uncomplicated by sub-plot or those “mysteries within mysteries” that can make this kind of fiction so rewarding.

The book is a quick read, where the interest is piqued by the setting, the location and the Asian heritage of one of the sleuths. We do get a quick glimpse into the realm of Chinese Australia -- enough to whet the appetite and make one ask, any chance for a proper exploration of this fascinating world in another book? 1920s Adelaide was a rich time in the development of city and state, and the author touches down lightly on history and culture. Take the lid off this melting pot, and you find quite a seething cauldron underneath … yes, another book??

The relationship between Billy and Tom is very subtle, very underplayed, which to me at least comes as something of a relief after the sex-heavy nature of books I’ve looked at recently. Billy and Tom have been lovers for a long time; there’s no reason for the author to include sex scenes. Their love life is alluded to, and several sweet romantic moments involve a kiss, a cuddle. This might not endear the usual reader of m/m, who likes the “romance” sizzling and exhaustively detailed. But for me, the underwritten relationship was a charming and welcome relief.

The research regarding police procedure and the legalities of the day is impeccable; this is the strength of the book, and L.J. LaBarthe credits her sources. The world of the 1920s was superficially similar to our own, but quite different at the detail level. The issues involving the Chinese community are about illegal gambling and opium smuggling. The issue more directly concerning Billy and Tom is the illegality of homosexuality. It was a prison offense in their day, and would remain so for decades more. (Readers shouldn’t be too quick to judge; homosexuality was illegal everywhere else, too! The world of 100 years ago had an “alien” quality that can astonish today, when you look too closely.)

More surprising was to find curious errors which a long-time resident of Adee notices at once. For instance, Billy and Tom visit a hotel near the Brighton Jetty, described as the Brighton Hotel. But the Brighton Hotel (recently renamed the Metro) is about 500 yards from the beach, on the corner of Brighton Rd. and Sturt Rd. The hotel by the jetty is the Esplanade Hotel. Elsewhere, the book refers to the Semaphore docks. There are no docks at Semaphore, and never were; there’s a looong jetty -- so long because the water is extremely shallow, far too shallow to dock ships onshore. (Don’t think about the marina on the “river.” It’s recent, and way too shallow for all but small boats.) The author makes reference to autumn, when “all the leaves would turn red and gold.” The thing is that the common trees here aren’t deciduous; gum trees don’t change color. There’s also a very curious reference to the “governor” fleecing the people twice via the gold tax. In this country, though any state does have a governor, it’s merely a ceremonial office, not a political one. The state governor is a representative of the Crown; the authority responsible for any tax would be the head of government -- the State Premier. (Or, if the tax were federal, the Prime Minister.) The use of “governor” here is an Americanism…

In fact, many Americanisms appear in the narrative, and jar local ears. For example, a fishing rod becomes a “fishing pole.” Down here, we say “laundry,” never “laundry room.” Where an American would say “produce,” we always said “fruit and veg,” until very recently, when the Americanism is indeed infiltrating the local language. The other oddity is in the use of the word “delicatessen,” and this one will be misleading to US readers. Here, the store is called a “deli,” and is very different indeed from what Americans know as a delicatessen. A deli is the equivalent of the British “street corner shop.” Like a pocket-size convenience store -- not a smallgoods shop/store.

Such discrepancies would have made me assume the author was American -- perhaps someone who visited down here, fell in love with the place, and longs to return one day. The author’s bio says she lives here, which makes the narrative all the more curious -- do I perceive the hand of an editor, changing wording and actually installing mistakes? I’d have expected a local writer to wax rhapsodic, but L.J. LaBarthe doesn’t take a moment to describe the beautiful colonial and post-colonial architecture … and Billy makes a strange observation about waiting for the cool of autumn to come in, right on the heels of summer; but the first month of autumn (March) in Adelaide is as hot as, or hotter than summer, and a change in the weather brings humidity and storms. I’m so surprised to learn the author is local.

Details aside, The Body on the Beach is a very readable book with a clear, no-frills style of writing that’s only a little repetitive here and there. If I have a major quibble with the style, it’s that the dialog is what I can only term as “naïve,” meaning bland, faultlessly polite throughout, with unfailing bonhomie which has the effect of making it unrealistic. No one gets peeved; no one has a dialect; everyone has the same “voice.” If there’s one thing the author needs to work on, it’s dialog. (Also the social niceties. Billy’s manservant, Jian, alternately addresses Tom as Mister Williams, Master Tom, or just plain Tom. Either of the first two would have been acceptable, but a servant would never be familiar.)

The Body on the Beach is at its best when Billy is dealing with his own people and a door cracks opens onto their world … smoky, dim, dangerous, just a little bit alien, with the leftover reek of opium and the half-heard ruckus of a fan-tan game in progress.

There’s also the fading echoes of the rough world of the goldfields, the touch of the exotic, where past and present seem to impinge, and where ambition, greed, can so easily turn to murder. Full marks to Ms. LaBarthe for digging into the research and having the vision to explore this era, which has seldom been touched on, even in mainstream fiction.

If you can live with the bland, genteel dialog, and if you’re not local to Adelaide, and so won’t notice the gaffs, the plot is interesting and the characters are charming -- in fact, they’re charming enough that I’d like to see another book where the author properly explores the domestic arrangement in which Billy’s wife is as fond of Tom as of Billy, and where the fascinating world of Chinese Australia is plumbed. If I were awarding stars, I’d be giving The Body on the Beach about 3.75, warts and all, because under the umbrella of m/m as understood today, it’s a small miracle this book (at long last, a real, genuine story involving gay protagonists, which has nothing to do with sex!) was written at all … and I’m very glad it was. There’s a lot to like about it: it’s different, the setting is delightful, the characters likeable, and the Chinese connection delicious. The potential for development is immense -- another book, perhaps?

|